Mental Health Resources

The COVID-19 pandemic is taking a terrible toll on the health and well-being of youth and young adults. Already alarming rates of depression, suicide, and anxiety are exacerbated by the isolation, contact restrictions, and economic challenges brought on by the pandemic. Black, Indigenous, and other youth of color (BIYOC); youth involved in the foster care and juvenile justice systems; and other traditionally underserved youth already are impacted at levels worse than their white or non-system involved peers, further hindering their ability to survive and thrive during the pandemic. As traditionally underserved youth navigate the pandemic, all systems need to develop and implement innovative strategies to address their existing and emerging health and mental health needs.

Addressing Mental Health Disparities During the Pandemic

Before COVID-19, the American Psychological Association estimated that 15 million youth have a diagnosable mental health disorder. Over 80 percent of youth in need of mental health services do not receive services in their communities, with BIYOC and LGTBQ youth the most likely groups not to receive needed care. School-based health centers in urban areas were 21 times more likely to provide mental health services than community-based providers. With schools closed, youth who receive their mental health services in their schools now need to find alternatives to care.

School-based mental health providers such as school counselors, nurses, social workers, and psychologists remain the first point of contact for students who are depressed, isolated, anxious, and now those traumatized by the pandemic. The American School Counselor Association and the National Association of School Psychologists developed a school reentry guide advising their members to develop cross-system plans that engage school and community resources. A key recommendation is to map available resources and needs to address short- and long-term needs, including repositioning staff to where they are needed most. School leaders are also learning how to leverage technology to meet the social, emotional, and mental health needs of middle and high school students.

Establishing partnerships with community-based mental health providers is a strategy already increasingly used to meet the mental health needs of BIYOC students. In Washington, DC, the Achievement Preparatory Academy is partnering with the AprilMay Company, Inc., a local behavioral health organization, to provide social-emotional and mental health services to their students. Teachers and counselors recognized the pandemic added multiple stressors to families already struggling to meet basic needs. To help students and families cope, they expanded access to mental health services, from the individual and small group services offered prior to the crisis, to any student, teacher, or family member using telemedicine resources.

Schools are also leveraging resources from organizations like The Trevor Project to supplement the services they provide for at-risk students. In the second annual National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health 2020, The Trevor Project reports almost 70 percent of LGBTQ youth have experienced anxiety in the past two weeks, and nearly half report they wanted but were not able to access mental health services in the past year. To address these and other needs, The Trevor Project offers a wide range of services, including the TrevorLifeline for crisis counseling, TrevorChat and TrevorText which provide access to counselors, and TrevorSpace, whichis an online international peer-to-peer community for LGBTQ young people and their friends.

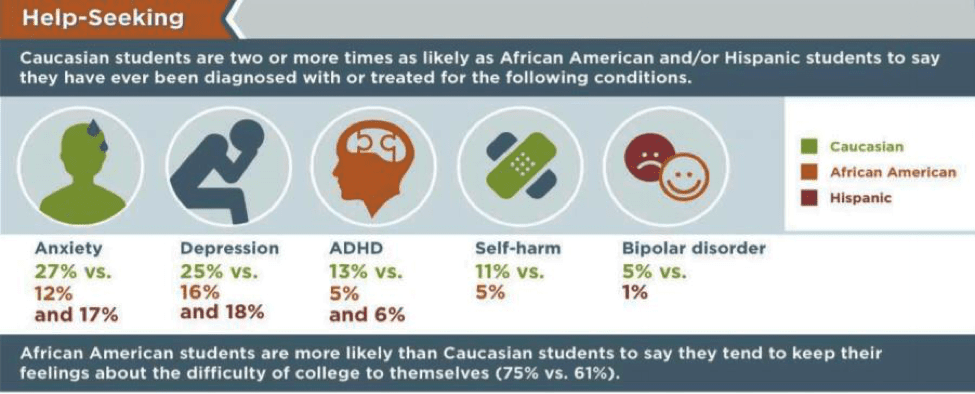

The Steve Fund provides support for college-age BIYOC students through its crisis text line. They, along with their partner The Jed Foundation, assist higher education institutions in developing an Equity in Mental Health Framework composed of actionable strategies they can implement to bridge mental health disparities facing students of color. The framework was developed in response to data they collected that revealed that college students of color were almost twice as likely not to seek help when they feel depressed or anxious compared to white students. They also found that only 28 percent of students of color found their campuses inclusive, compared to 45 percent of their white peers. As a result, nearly half reported feeling isolated on campus. These data reveal that attention to the mental health needs of students of color persists into the higher education learning experience.

System-Involved Youth at High Risk for COVID-19

For the roughly 48,000 youth held in juvenile detention facilities across the United States, the COVID-19 pandemic is also proving especially concerning. Black and Indigenous youth are overrepresented in juvenile facilities, with Black boys and Black and Indigenous girls, extremely overrepresented relative to their share of the total youth population. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth, and youth currently or previously involved with the foster care system are also overrepresented in the juvenile justice system. Even before the pandemic, youth detention facilities failed to adequately address the health and mental health needs of BIYOC and LGBTQ youth. These uniquely vulnerable youth often come to juvenile facilities with a host of pre-existing needs such as physical or sexual abuse, accidents, serious illness, and violence. These traumatic events often lead to depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Unfortunately, most facilities are ill-equipped to address their needs with only 53 of 3,500 juvenile justice residential facilities in the United States having received accreditation for the health care they provide. Coincidentally, calls to end the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion would require standards to ensure quality health care services in juvenile and adult detention facilities.

While many youth have been released or diverted from detention as a result of the pandemic, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) joins juvenile justice reform advocates in the call for incarcerated youth to receive “…special consideration in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.” Specifically, the Academy is asking that state agencies craft pandemic plans that release youth from custody who can be safely cared for in their communities. Before they are released, a comprehensive transition plan should be developed to include screening for health and mental health needs and restoring health benefits lost during incarceration. Community-based organizations providing youth reentry services should receive additional funding to provide virtual and in-person services, with appropriate safety precautions. For the youth who remain incarcerated, every effort should be made to ensure their safety, including improved hygiene practices, social distancing that is not solitary confinement, coronavirus testing, and a continuation of any health and mental health services they were receiving before the pandemic.

Resources for Policymakers and Practitioners

The undeniable disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Black, Indigenous, and other youth of color (BIYOC); youth involved in the foster care and juvenile justice systems; and other traditionally underserved youth requires a targeted response. Federal, state, and local governments must enact policies and implement evidence-based programs that protect and support vulnerable youth during and after the immediate pandemic crisis. AYPF has created a COVID-19 Information Hub that provides useful resources for youth most at risk. We will continue to update this information hub and invite your active participation in planned learning events as we explore strategies from the AYPF peer network.

- Week 1: Justice-Involved Youth

- Week 2: English Language Learners (ELL)

- Week 3: Youth in Foster Care

- Week 4: Rural Populations

- Week 5: First-Generation College Students

- Week 6: Youth with (Dis)abilities

- Week 7: Resources for Parents

- Week 8: Youth Experiencing Homelessness

- Week 9: Social Emotional Learning (SEL)

- Week 10: Resources related to Reopening of Schools

Have a girl in grades 3rd – 12th? Both of you can experience Girls Empowerment Network’s live programs and resources from the comfort of your own home. Do a quick tutorial, download an activity, or connect with others in our network through a live workshop to combat stress, anxiety or anything that may be on your mind.

LOCAL SUPPORT AND RESOURCES

Anyone currently experiencing COVID-19 symptoms should contact their healthcare provider. Harris County residents without access to healthcare can call the triage line for COVID-19-related questions at 713.634.1110 from 9am-7pm, 7 days a week. For more information on COVID-19, please go to www.ReadyHarris.org or www.hcphtx.org.

Harris County/Houston Self-Assessment Tool: Determine whether you may need further assessment or need to be tested for COVID-19.

Coronavirus: Houston Health Updates

Houston Food Bank: Find a partner near you, apply for SNAP, call their helpline at 832.369.9390 or text FOOD to 855.308.2282 to find your nearest food pantry.

Houstonians with disabilities can still contact MOPD staff for referrals and constituent services by calling 832.394.0814 or by emailing mopdmail@houstontx.gov during normal business hours.

LOCAL CORONAVIRUS HOTLINES

For Harris County Residents:

The Harris Center’s Harris County COVID-19 Mental Health Support Line: 833-251-7544 (Available 24/7)

Harris County Public Health: 832-927-7575* (*This number is staffed 9 a.m. to 7p.m. everyday)

Harris Health System: 713-634-1110* (*This number is 9am-7pm, everyday clinical-related questions only)

For City of Houston Residents:

Houston Health Department: 832-393-4220* (*This number is staffed 9 a.m. to 7p.m. M-F, 9am-3pm on Sat.)

For Fort Bend County Residents:

Fort Bend County Health & Human Services: 281-633-7795* (*This number is Monday-Friday from 8:00am to 5:00pm)

For questions about COVID‑19, including finding a doctor or accessing medical care, dial 2‑1‑1, then choose Option 6.

(Hours: 7:00 a.m. – 8:00 p.m., 7 days per week)